Type D Personality Individuals: Exploring the Protective Role of Intrinsic Job Motivation in Burnout

[Trabajadores con personalidad tipo D: la exploraciĂłn del rol protector de la motivaciĂłn laboral intrĂnseca en el burnout]

Esther Cuadrado1, 2, Carmen Tabernero1, 3, 5, Cristina Fajardo2, Bárbara Luque1, 2, Alicia Arenas1, 4, Manuel Moyano1, 2, Rosario Castillo-Mayén1, and 2

1Maimonides Biomedical Research Institute of Cordoba (IMIBIC), Spain; 2University of Cordoba, Spain; 3University of Salamanca, Spain; 4University of Seville, Spain; 5Neurosciences Institute of Castilla y LeĂłn (INCyL), Spain

https://doi.org/10.5093/jwop2021a12

Received 29 January 2021, Accepted 12 May 2021

Abstract

Three studies (Study 1, with 354 teaching and administrative staff at the University of Córdoba, Study 2 with 567 teachers, Study 3, longitudinal, with 111 teachers) analyzed the role adopted by self-regulatory variables in the relationship between type D personality (TDP) and burnout. Moderated mediation analyses in the three studies confirmed: (1) the mediating role of emotional dissonance in the relationships between TDP and burnout; (2) the mediating role of self-efficacy in the TDP-burnout link; and (3) the moderating role of intrinsic job motivation in confirmed mediations. The results highlighted that (1) high levels of emotional dissonance may act as a risk factor that is increased with high levels of TDP and (2) self-efficacy to cope with stress and intrinsic motivation act as protective factors, highlighting the protective role of intrinsic motivation because it buffers the negative effects of TDP on workers’ burnout.

Resumen

En tres estudios diferentes (estudio 1 con 354 participantes, personal docente y administrativo de la Universidad de Córdoba, estudio 2 con 567 docentes y estudio 3, de carácter longitudinal, con 111 docentes) se analiza el papel que adoptan las variables autorreguladoras en la relación establecida entre la personalidad tipo D (PTD) y el burnout. Los análisis de mediación moderada confirmaron en los tres estudios: (1) el papel mediador de la disonancia emocional en las relación que establece la PTD con el burnout, (2) el papel mediador de la autoeficacia en la asociación PTD-burnout y (3) el papel moderador de la motivación laboral intrínseca en las mediaciones confirmadas. De los resultados se destaca que (1) un nivel elevado de disonancia emocional puede actuar como un factor de riesgo que aumenta con un nivel elevado de PTD y (2) la autoeficacia en el afrontamiento de situaciones de estrés y la motivación intrínseca actúan como factores protectores, destacando el rol protector de la motivación intrínseca, que amortigua los efectos negativos que ejerce el PTD en el burnout de los trabajadores.

Palabras clave

Burnout, Personalidad tipo D, Disonancia emocional, Autoeficacia para el afrontamiento del estrĂ©s, MotivaciĂłn laboral intrĂnsecaKeywords

Burnout, Type D personality, Emotional dissonance, Self-efficacy to cope with stress, Intrinsic job motivationCite this article as: Cuadrado, E., Tabernero, C., Fajardo, C., Luque, B., Arenas, A., Moyano, M., & Castillo-Mayén, R. (2021). Type D Personality Individuals: Exploring the Protective Role of Intrinsic Job Motivation in Burnout. Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 37(2), 133 - 141. https://doi.org/10.5093/jwop2021a12

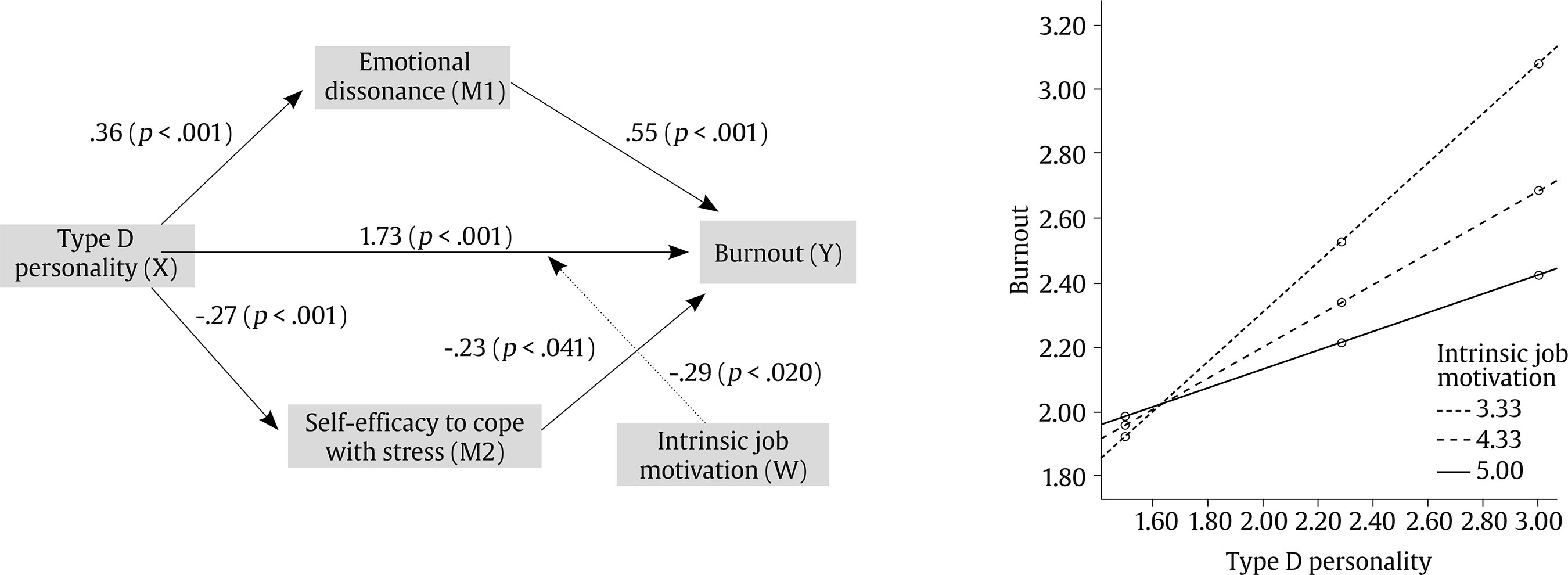

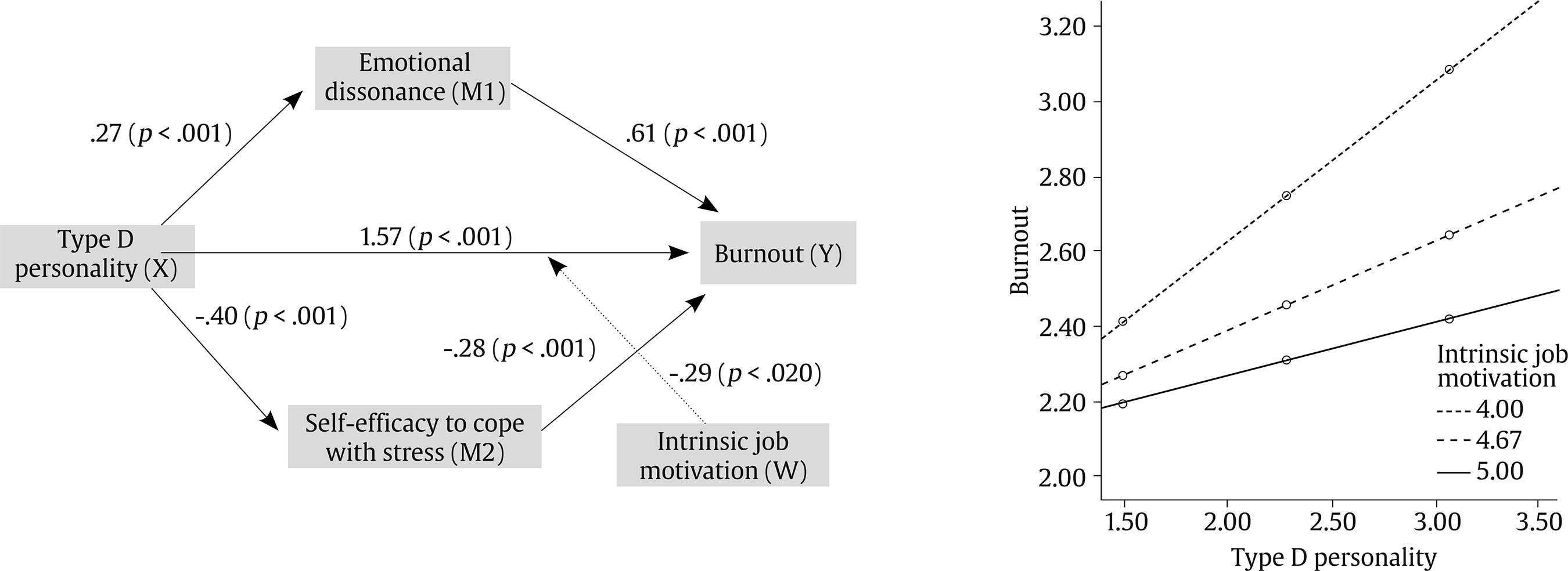

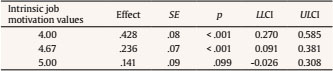

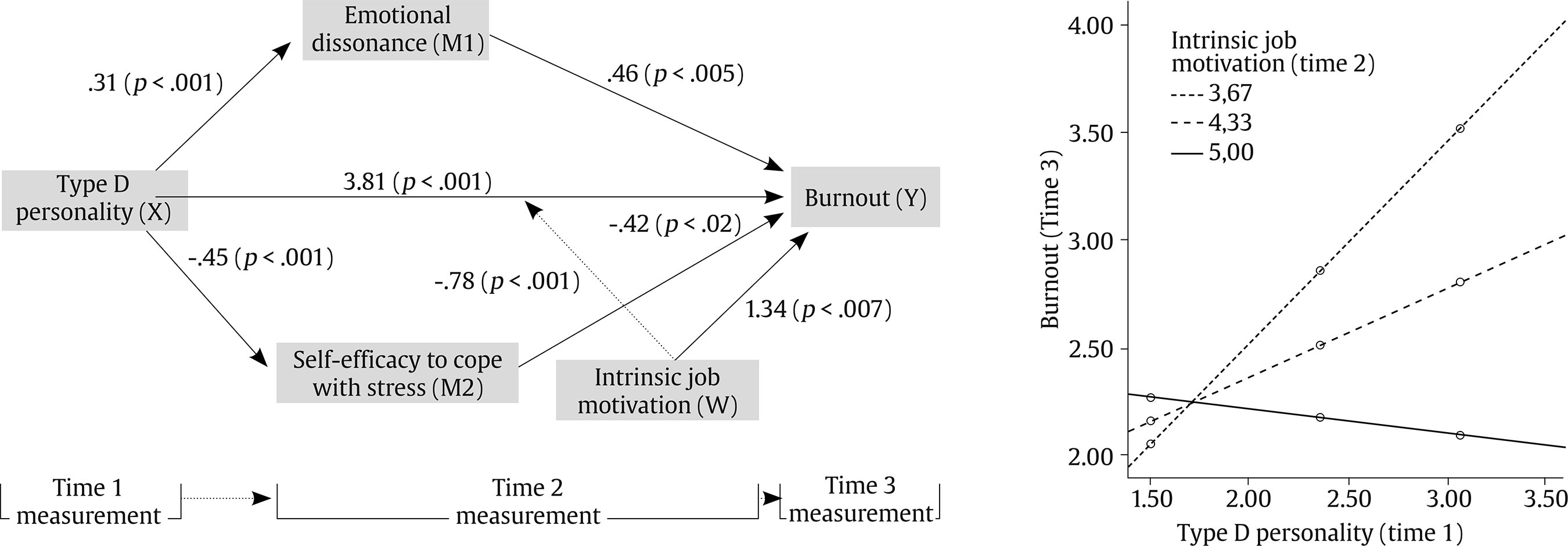

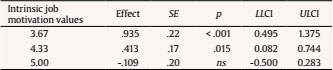

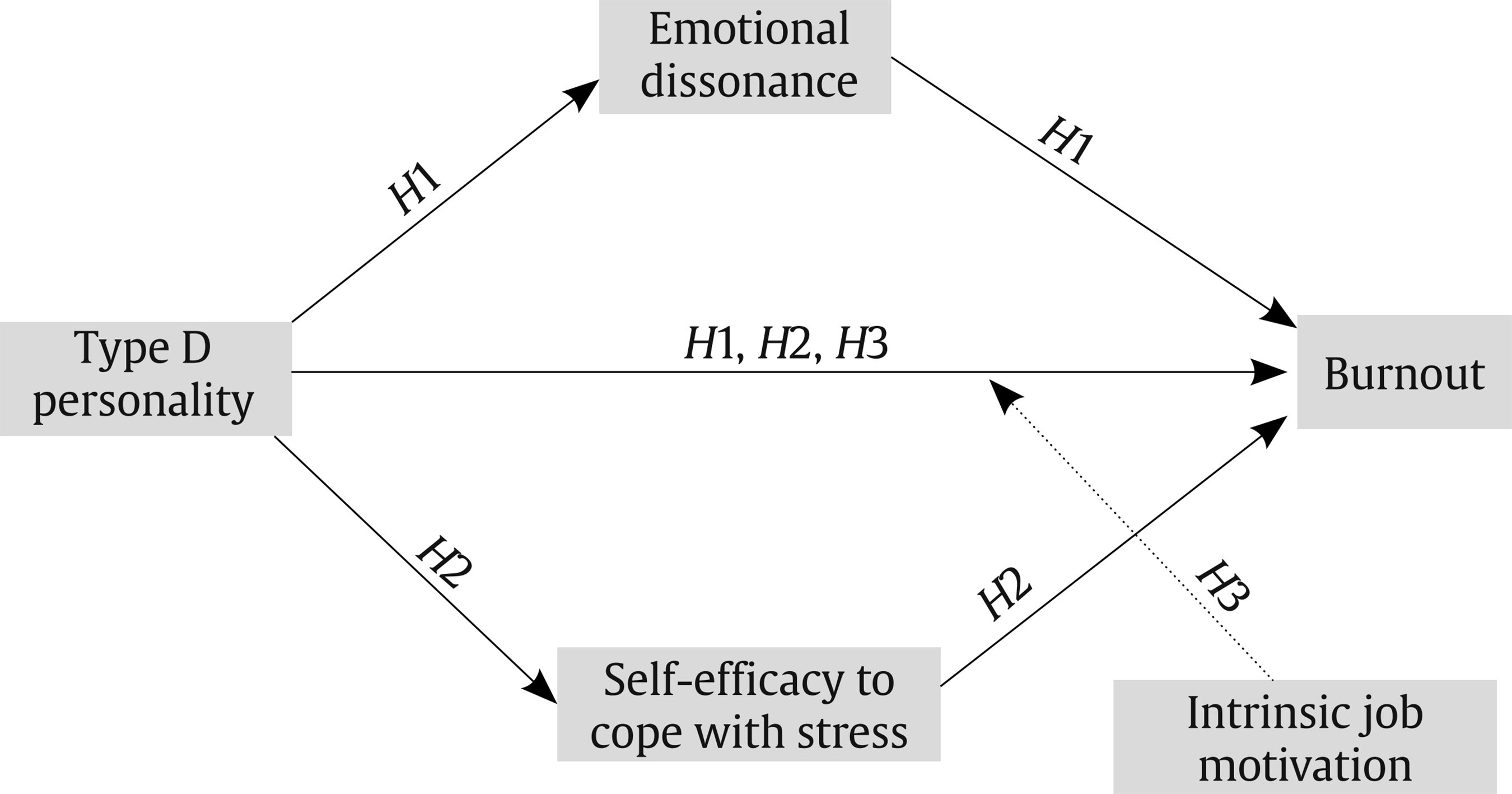

esther.cuadrado@uco.es Correspondence: esther.cuadrado@uco.es (E. Cuadrado); rcmayen@uco.es (R. Castillo-Mayen)., esther.cuadrado@uco.es Correspondence: esther.cuadrado@uco.es (E. Cuadrado); rcmayen@uco.es (R. Castillo-Mayen).Currently, total labor force—who contributes to the economic and social development of each country—constitutes half of the world’s population (International Labour Organization [ILO, 2019]). According to the labor force survey of the Spanish National Institute of Statistics (2019), 58.74% of the Spanish population is working. Thus, work has a central role in people’s life and health. Nevertheless, 59% of the Spanish labor force suffers from work stress, and 60% of work leave in Europe is related to psychosocial risks and job-related stress (European Agency for Safety and Health at Work [EASHW, 2013]). Moreover, the observed increase in the prevalence of burnout is a relevant problem in the world (Grensman et al., 2018). Prolonged stressful situations at work gradually reduce workers’ ability to cope with stress using resources (Shirom, 2003). These situations may lead individuals to emotional, physical, and mental exhaustion, and may undermine their ability to maintain an intense activity at work (Schaufeli et al., 2009), triggering the affective-behavioral response known as burnout syndrome. This syndrome is actually caused by excessive levels of continued stress and a mismatch between demands and labor resources (Schaufeli et al., 2009; Tucker et al., 2012). Burnout is thus associated with a prolonged imbalance between work demands and coping resources. Authors refer to three dimensions of burnout: emotional exhaustion, cynicism, and feelings of inefficiency (Lee & Ashforth, 1993; Leiter et al., 2015; Maslach & Leiter, 2016, 2017; Schaufeli et al., 2009). Emotional exhaustion and cynicism are conceived as the core components of this syndrome (Caballero et al., 2007; Green et al., 1991; Salanova et al., 2001; Salanova et al., 2005; Schaufeli & Taris, 2005); meanwhile, a feeling of efficiency may be conceived as a personal resource that protects individuals from burnout (Caballero et al., 2007; Salanova et al., 2001; Salanova et al., 2005). This syndrome constitutes a labor risk itself and has several consequences that extend to personal, social, organizational, and economic spheres (Gil-Monte, 2005; Hamaideh, 2011; Maslach & Leiter, 2017). It has been related to both physical and psychological symptoms (Gil-Monte, 2005; Ríos Rísquez et al., 2011). People suffering from burnout usually drop out for a long time, show decreased productivity and performance, have an increase in their error rate and the number of accidents and injuries at work, and suffer absenteeism and depression. All of this affects the quality of service offered and can lead to large economic losses for companies (Gil-Monte, 2005; Grensman et al., 2018; Hamaideh, 2011; Kim et al., 2016; Yoshizawa et al., 2016). This highlights the importance of knowing and addressing the risk and protective factors that are related to core components of burnout, in order to understand how burnout occurs and learn how to prevent it. Type D Personality and Burnout The fact that different people who are in the same environment and are exposed to the same work stressors do not feel the same levels of burnout has led to highlighting the relevance of individual factors in the development of this syndrome (Geuens et al., 2015). A personal variable that is currently being studied is type D personality (TDP; Denollet, 2005), a personality trait characterized by a blend of negative emotions (negative affectivity) and the inhibition of these emotions in social situations (social inhibition). TDP has been associated with worse physical and psychological health (Kasai et al., 2013; Ogińska-Bulik, 2006). In the same way, individuals with TDP have been shown to have significantly lower levels of self-efficacy, to use worse coping strategies, to perceive less social support (Molloy et al., 2012; Polman et al., 2010; Shao et al., 2017), and to present more emotional dissonance (Karatepe & Aleshinloye, 2009). The relationships that TDP and its negative affect component establish with these variables could explain the results of some studies that have affirmed that people with TDP perceive work environment as more stressful and present greater burnout (Armon, 2014; Geuens et al., 2015; Mols & Denollet, 2010; Ogińska-Bulik, 2006; Polman et al., 2010; van den Tooren & Rutte, 2016). In this sense, according to these studies, we expected a positive relationship between TDP and burnout. Self-regulating Variables and Burnout: Emotional Dissonance, Self-efficacy to Cope with Stress, and Intrinsic Job Motivation Emotional dissonance and burnout. One part of emotional work is that workers regulate their emotions and expressions to meet an organization’s visualization standards. When there is a discrepancy between emotions that must be shown in a worker’s role and felt emotions, emotional dissonance appears (Van Dijk & Brown, 2006). This emotional dissonance is obviously a relevant source of tension (Totterdell & Holman, 2003). In this sense, there is an extensive literature relating emotional dissonance with burnout (Andela et al., 2016; Andela & Truchot, 2017; Karatepe & Aleshinloye, 2009; Kenworthy et al., 2014). These studies have highlighted emotional dissonance as a relevant predictor of burnout suffered by workers in the service sector, so that the greater the discrepancy that an individual perceives between the emotions he or she experiences at work and the emotions he or she can show to users, the greater the burnout experienced in the workplace. This relationship has been demonstrated in a wide variety of professions, such as flight attendants, nurses, police officers, hotel staff, and other types of work in the service sector (Bakker & Heuven, 2006; Diestel & Schmidt, 2011; Heuven & Bakker, 2003; Karatepe, 2011; Kwack et al., 2018; Schaible & Gecas, 2010). On the other hand, Karatepe and Aleshinloye (2009) observed that emotional dissonance not only was positively related to negative affect and burnout, but that emotional dissonance also mediated the relationship between these variables. In the same vein, emotional dissonance has also been related to TDP (Bakker & Heuven, 2006; Diestel & Schmidt, 2011; Heuven & Bakker, 2003; Karatepe, 2011; Schaible & Gecas, 2010), which is related to burnout (Armon, 2014; Geuens et al., 2015; Ogińska-Bulik, 2006; Polman et al., 2010; van den Tooren & Rutte, 2016). Thus, if TDP is related to emotional dissonance (Bakker & Heuven, 2006; Diestel & Schmidt, 2011; Heuven & Bakker, 2003; Karatepe, 2011; Schaible & Gecas, 2010) and burnout (Armon, 2014; Geuens et al., 2015; Mols & Denollet, 2010; Ogińska-Bulik, 2006; Polman et al., 2010; van den Tooren & Rutte, 2016), and if emotional dissonance is also related to this syndrome (Andela & Truchot, 2017; Andela et al., 2016; Karatepe & Aleshinloye, 2009; Kenworthy et al., 2014), we hypothesized that emotional dissonance would mediate the relationships of TDP with core components of burnout. Self-efficacy to cope with stress and burnout. Bandura (1997, 2006) proposed that self-efficacy moderates the effect of work stressors, because people who perceive themselves as effective carry out more active coping strategies and perceive stressful situations as a challenge. Several studies that have explored the nexus between self-efficacy and burnout have also found the moderating role adopted by self-efficacy in the relationships between stressful situations and burnout (Gismero-González et al., 2012; Khani & Mirzaee, 2015; Merino Tejedor & Lucas Mangas, 2016). Other studies have found direct predictive effects between self-efficacy—both general and occupational—and burnout (Federici & Skaalvik, 2012; Merino Tejedor & Lucas Mangas, 2016; Sánchez et al., 2006; Shoji et al., 2016). For example, Federici and Skaalvik (2012) studied the relationship of occupational self-efficacy with burnout in a sample of school directors. Their results showed that directors with less self-efficacy suffer more burnout, because they doubted their abilities to carry out important tasks and responsibilities. Thus, if general self-efficacy has been related to stress and burnout, and based on Bandura's (1997) contention that specific self-efficacy influences the specific behavior to which it refers, it can be expected specific self-efficacy to cope with stress will predict lower levels of burnout. Therefore, we propose that—because TDP has been positively related to stress (Ogińska-Bulik, 2006) and negatively related to coping and some types of self-efficacy (Molloy et al., 2012; Polman et al., 2010; Shao et al., 2017)—it is possible that TDP and self-efficacy to cope with stress will also be negatively related. In turn, because general self-efficacy has been shown to be related to burnout (Gismero-González et al., 2012; Khani & Mirzaee, 2015; Merino Tejedor & Lucas Mangas, 2016; Shoji et al., 2016), and according to Bandura's (1997) contention that specific self-efficacy related to a specific behavior predicts such behavior and results in better than general efficacy, we hypothesized that self-efficacy to cope with stress would mediate the TDP–burnout link. Intrinsic job motivation and burnout. Ryan and Deci (2000) proposed the theory of self-determination to explain the reasons why people engage in specific activities. This theory established a motivational continuum, distinguishing three levels: demotivation, extrinsic motivation, and intrinsic motivation (Ryan & Deci, 2000). In this regard, individuals who are intrinsically motivated will concentrate and persevere more in their tasks. In addition, intrinsic motivation is conceived as one of the personal resources to cope with stress and burnout (Karatepe & Aleshinloye, 2009). In fact, several studies have shown that people with high intrinsic motivation are increasing their personal resources and are more protected from the negative effects of stress and burnout (David, 2010; Fernet et al., 2010; Karatepe & Aleshinloye, 2009; ten Brummelhuis et al., 2011). Finally, the moderating effect of intrinsic motivation has also been analyzed. Fernet et al. (2010) studied the relationship between social support and burnout and found that not all participants reacted equally to good interpersonal relationships at work: good interpersonal relationships were a more protective factor from burnout when people were not intrinsically motivated to do their tasks; in contrast, individuals with high intrinsic motivation did not benefit so much from the effect of such relationships because their self-determination was sufficient to protect them from burnout. Moreover, Trépanier et al. (2013) have shown that intrinsic motivation moderated the relationship between three types of labor demands and psychological distress, because highly motivated individuals were less likely to see the demands as stressful. Therefore, based on the moderating effects that intrinsic motivation has shown in the relationship of different variables with burnout (Fernet et al., 2010; Trépanier et al., 2013), we propose that intrinsic motivation could act as a moderator in the relationship of TDP with burnout, reducing the negative effects of TDP on the studied syndrome. Thus, based on the literature, we hypothesized that intrinsic self-determination would be necessary to protect individuals with high TDP characteristics from burnout. Objectives and Hypotheses The objectives of this study are, on the one hand, to analyze the predictive role of some potential psychosocial determinants of core components of burnout (TDP, emotional dissonance, self-efficacy to cope with stress, and intrinsic job motivation), as well as the mediating and moderating relationships that may exist among these determinants. Specifically, the following hypotheses are posited: Hypothesis 1: Emotional dissonance mediates the relationship between TDP and burnout. Hypothesis 2: Self-efficacy to cope with stress mediates the relationship between TDP and burnout. Hypothesis 3: Intrinsic job motivation moderates the relationship between TDP and burnout, so that the mediations established in Hypotheses 1 and 2 are moderated by intrinsic job motivation. The different hypotheses can be observed graphically in Figure 1. It is known that the incidence of burnout is different according to the job, taking place to a greater extent in jobs that require direct and continuous contact with the users of services they offer (Gil-Monte, 2005; Lee & Ashforth, 1993; Patlán-Pérez, 2013; Schaufeli et al., 2009; Vldu & Kállay, 2010). The highest prevalence in these kinds of jobs is due to the great emotional burden that the professional–user relationship carries, which can be very stressful for employees, as they have to adjust continually to others’ needs (Gil-Monte, 2005). To confirm these hypotheses, the study will be performed in a sample of professionals who usually suffer from stress and burnout, professionals who work face to face with their users. In this case, the sample will consist of professionals at the University of Córdoba (Spain), both teaching and research staff and services and administrative staff. Method Participants. The sample consisted of 354 participants (53.8% women and 46.1% men) with a mean age of 47.28 years (SD = 9.12, range = 21-68). With respect to the their job, 54.8% form part of the teaching and research staff, while 45.2% are part of the administrative and services staff. The mean length of tenure in the position was 11.26 years (SD = 10.2, range = 1-42), while the mean length of tenure in the job was 16.99 years (SD = 10.91, range = 1-44). Instruments. To describe the sample, some socio-demographic variables were assessed (age, sex, job, length of tenure in the position and in the job). Then, psychological variables were measured with a 5-point Likert scale. Emotional dissonance (α = .85). The perception that professionals have to the effect that their work generates emotions that are different from what they should demonstrate to their users was measured with the Emotion-Rule Dissonance Scale (Bakker et al., 2003). Self-efficacy to cope with stressful situations (α = .91). The extent to which professionals feel able to cope with stress effectively was measured with the Self-efficacy to Cope with Stressful Situations Scale (Tabernero et al., 2009). Intrinsic job motivation (α = .90). The extent to which the staff was intrinsically motivated by their job was measured with the three items of the intrinsic job motivation factor of the Multidimensional Work Motivation Scale (Gagné et al., 2015). Type D personality (α = .83). The components of negative affectivity and social inhibition of the TDP were measured with the Type D Personality Scale (Denollet, 2005). Burnout. The core components of the burnout syndrome suffered by the participants were measured with the mean of the two core components of Maslach’s Burnout Inventory General Scale (Gil-Monte, 2002). The internal consistency for each burnout subcomponent was high (α = .86 for emotional exhaustion and α = .84 for cynicism). The global scale also obtained good reliability (α = .90). Procedure. Once the Research Ethics Committee of Andalucia approved the study, and by using a convenience sampling method, the administrative team of the chancellor of the University of Cordoba sent to all university staff members an email that included a link to the online questionnaire (generated with Unipark Questback). Access to the questionnaire required informed consent from all participants. Data analysis. Hierarchical linear regression analyses were performed to determine what percentage of variance was explained by the predictive variables. To evaluate the mediation and moderation hypotheses, a moderated mediation analysis was performed, by using model 5 of Process for SPSS (Hayes & Preacher, 2013), with 10,000 bootstrap resamples and a confidence interval of 95%. Burnout was introduced as the dependent variable, TDP as the independent variable, emotional dissonance and self-efficacy to cope with stress as mediating variables, and intrinsic job motivation as the moderating variable. Results Preliminary analyses. Pearson’s correlation analyses showed that all the variables were related in the expected direction. Participants with higher scores on burnout presented higher scores on TDP (r = .43, p < .001) and emotional dissonance (r = .42, p < .001), as well as lower scores on self-efficacy to cope with stress (r = -.24, p < .001) and intrinsic job motivation (r = -.26, p < .001). The results of the hierarchical linear regression analyses showed that the model explained 29% of the variance, R2adj = .29, ρ2 [estimator of the squared population multiple correlation coefficient calculated with Pratt formula; Yin & Fan, 2001] = .30; F (4, 247) = 26.85, p < .001, and that all the variables acted as direct predictors of burnout core. Intrinsic job motivation was a moderator in the mediating effect of emotional dissonance and self-efficacy to cope with stress in the relationship between TDP and burnout. As can be seen in Figure 2, the results confirmed the moderated mediation hypotheses, the final model explaining 32% of the variance, R2 = .32 F(5, 246) = 22.97, p <.001. The analysis performed showed, on the one hand, that both emotional dissonance (indirect effects: bootstraps, 95% CI = .137 [.072, .209]) and self-efficacy to cope with stress (indirect effects: bootstraps, 95% CI = .032 [.001, .077]) mediated the relationship between TDP and burnout syndrome, confirming Hypotheses 1 and 2, respectively. On the other hand, the moderating role of intrinsic job motivation in the relationship between TDP and burnout was demonstrated, test of unconditional interaction: ΔR2 = .015, F(1, 246) = 5.49, p = .020, confirming Hypothesis 3. Figure 2 Mediation of Emotional Dissonance and Self-efficacy to Cope with Stress in the Relationship between Type D Personality and Burnout, Moderated by Intrinsic Motivation, in a University Staff’s Sample.   Note. Coefficients are unstandardized. The conditional effects of the focal predictor (TDP) at the values of the moderator (intrinsic job motivation) can be seen in Table 1 and Figure 2. Table 1 Conditional Effect of Type D Personality on Burnout at the Values of Intrinsic Job Motivation   Note. SE = standard error; p = p-value; LLCI = lower level for 95% confidence interval; ULCI = upper level for 95% confidence interval. Discussion The results of Study 1 confirmed that all the variables adopted a relevant role in predicting burnout, being TDP and emotional dissonance risk factors, whereas self-efficacy to cope with stress and intrinsic job motivation were protective factors. Thus, the results highlighted the relevance of considering those variables in psychosocial interventions adopted by the organizations in order to reduce burnout in their employees. Moreover, the moderated mediations hypothesized were confirmed. First, both emotional dissonance and self-efficacy to cope with stress mediated the relation of TDP with burnout. Thus TDP influences burnout both directly—congruent with previous research (Armon, 2014; Geuens et al., 2015; Mols & Denollet, 2010; Ogińska-Bulik, 2006; Polman et al., 2010; van den Tooren & Rutte, 2016) and indirectly, through its effect on two variables that directly affect burnout: emotional dissonance and self-efficacy to cope with stress. Thus, the more individuals have TDP characteristics, (a) the more they perceive high discrepancy between their emotions at work and the emotion they can show to their users, and (b) the less they feel able to cope effectively with stressful situations at work, and then the more they experience burnout. Those relations may be explained by the fact that negative affectivity and inhibition of these negative emotions that characterized individuals with TDP may orient individuals to a kind of avoidance behavioral pattern that prevents their ability from coping effectively with stressful and emotionally dissonant situations, resulting in even more burnout. Secondly, intrinsic job motivation moderated these links by buffering the relation of TDP with the studied syndrome. Thus, the results showed that although there were no differences in the burnout suffered by individuals with low levels of TDP when they were intrinsically motivated to a high or low degree, when they displayed high TDP levels, high levels of intrinsic job motivation were needed to reduce burnout levels. Although previous research has found a moderating role of motivation in the relations between other variables and burnout (Fernet et al., 2010; Trépanier et al., 2013), the moderating role of motivation in the TDP-burnout link has not been studied. This result is especially relevant, highlighting the importance of intrinsic job motivation, which has the power to reduce the negative impact of TDP on burnout. In the second study, we would replicate the results of Study 1 in a sample of primary and secondary schoolteachers, a job especially affected by burnout (Vidal & García, 2009). Replication of the results would reinforce confirmation of expected relations. Method Participants. The sample consisted of 567 participants (64.9% women and 35.1% men), with a mean age of 44.8 years (SD = 8.51, range = 23-69 years). With respect to their job, 10.4% were infant education teachers, 39.2% were primary education teachers, 49.9% were secondary education teachers, and 0.5% were adult education teachers. Mean tenure in the position was 16.75 years (SD = 9.57, range = 1-51 years). In addition, 96.5% of teachers worked in a public institution, 3.2% in a charter school, and 0.4% in private schools. All participants worked in Andalucia, 27.9% being from Córdoba, 16.9% from Sevilla, 12.9% from Cádiz, 12.3% from Granada, 9.9% from Huelva, 9.5% from Jaen, 8.8% from Málaga, and 1.8% from Almería. Instruments, procedure, and data analysis. The same instruments of Study 1 were employed. As in Study 1, in Study 2 the reliability of all the scales was high, with Cronbach’s alpha values between .79 and .92. Once the Research Ethics Committee of Andalucia approved the study, and by using a convenience sampling method, different schools from Andalucia were contacted via email, requesting dissemination of the questionnaire. The email included a link to the online questionnaire (conducted through the Unipark Questback platform), beginning with informed consent from all participants. The same data analyses of Study 1 were employed. Results Preliminary analyses. Pearson’s correlation analyses showed that all variables were related in the expected direction. Participants with higher scores on burnout presented higher scores on TDP (r = .41, p < .001), and emotional dissonance (r = .44, p < .001) as well as lower scores on self-efficacy to cope with stress (r = -.37, p < .001) and intrinsic job motivation (r = -.44, p < .001). The results of the hierarchical linear regression analysis performed to explore the predictive value of independent variables over burnout showed that the model explained 38% of the variance, R2adj = .38, ρ2 = .38, F (4, 562) = 86.94, p < .001, and that, as in Study 1, all the variables acted as direct predictors of burnout. Intrinsic job motivation as moderator in the mediating effect of emotional dissonance and self-efficacy to cope with stress in the relationship between type D personality and burnout. As can be seen in Figure 3, as in Study 1, the results confirmed the moderated mediation hypothesis, the final model explaining 40% of the variance, R2 = .40, F(5, 561) = 73.34, p <.001. The analysis showed, on the one hand, that both emotional dissonance (indirect effects: bootstraps, 95% CI = .089 [.062, .119]) and self-efficacy to cope with stress (indirect effects: bootstraps, 95% CI = .062 [.026, .104]) mediated the relationship between TDP and burnout syndrome, confirming Hypotheses 1 and 2, respectively. On the other hand, the moderating role of intrinsic job motivation in the relationship between TDP and burnout was demonstrated, test of unconditional interaction: ΔR2 = .013, F(1, 561) = 12.08, p < .001, by confirming Hypothesis 3. Figure 3 Mediation of Emotional Dissonance and Self-efficacy to Cope with Stress in the Relationship between Type D Personality and Burnout, Moderated by Intrinsic Motivation, in a Teachers’ Sample.   Note. Coefficients are unstandardized The conditional effects of the focal predictor (TDP) at the values of the moderator (intrinsic job motivation) can be seen in Table 2 and Figure 3. Table 2 Conditional Effect of Type D Personality on Burnout at the Values of Intrinsic Job Motivation   Note. SE = standard error; p = p-value; LLCI = lower level for 95% confidence interval; ULCI = upper level for 95% confidence interval. In the third study, we would replicate the results of Study 1 and 2 in a longitudinal sample of primary, secondary, and university schoolteachers. Replication of the results, in a longitudinal sample, would reinforce confirmation of expected relations. Method Participants. The sample consisted of 111 participants (57.3% women and 42.7% men), with a mean age of 45.30 years (SD = 8.68, range = 28-68 years). With respect to their job, 23.4% were primary education teachers, 44.1% were secondary education teachers, and 32.4% were university education teachers. Mean tenure in the position was 16.52 years (SD = 10.64, range = 1-43 years). All participants worked in Andalucia. Instruments, procedure, and data analysis. The same instruments of Study 1 were employed. As in Study 1, in Study 2 the reliability of all the scales was high, with Cronbach’s alpha values between .82 and .93. Once the Research Ethics Committee of Andalucia approved the study, and by using a convenience sampling method, different schools from Andalucia were contacted via email, requesting dissemination of the questionnaire. The email included a link to the online questionnaire (conducted through the Unipark Questback platform), beginning with informed consent from all participants. For the longitudinal design, the questionnaire was administrated for three consecutive times, with a 5-month lapse between each recollection of data. The dispositional variable (TDP) was measured only in the first evaluation because personality variables are expected to be stable over time. The other variables were measured in all three evaluation. The same data analyses of Study 1 and 2 were employed. For the analyses, TDP of the first evaluation, emotional dissonance, self-efficacy to cope with stress, and intrinsic job motivation of the second evaluation, and burnout of the third evaluation were used, in order to ensure the longitudinal design. Results Preliminary analysis. Pearson’s correlation analyses showed that all variables were related in the expected direction. Participants with higher scores on burnout in the third evaluation presented higher scores on TDP in the first evaluation (r = .41, p < .001), and higher scores on emotional dissonance in the second evaluation (r = .39, p < .001) as well as lower scores on self-efficacy to cope with stress (r = -.40, p < .001) and intrinsic job motivation (r = -.45, p < .001) in the second evaluation. The results of the hierarchical linear regression analysis performed to explore the predictive value of the independent variables on burnout showed that the model explained 35% of the variance, R2adj = .35, ρ2 = .37, F(4, 103) = 15.37, p < .001, and that, as in Study 1, all the variables acted as direct predictors of burnout (the beta value for TDP was marginal (p = .06). Intrinsic job motivation as moderator in the mediating effect of emotional dissonance and self-efficacy to cope with stress in the relationship between type D personality and burnout. As can be seen in Figure 4, as in Study 1 and 2, the results confirmed the moderated mediation hypothesis, explaining the final model 46% of the variance, R2 = .46; F(5, 102) = 17.54, p < .001). The analysis showed, on the one hand, that both emotional dissonance (indirect effects: bootstraps, 95% CI = .075 [.019, .140]) and self-efficacy to cope with stress (indirect effects: bootstraps, 95% CI = .099 [.026, .214]) mediated the relationship between TDP and burnout syndrome, confirming Hypotheses 1 and 2, respectively. On the other hand, the moderating role of intrinsic job motivation in the relationship between TDP and burnout was demonstrated, test of unconditional interaction: ΔR2 = .09, F(1, 102) = 16.80, p < .001, by confirming Hypothesis 3. Figure 4 Mediation of Emotional Dissonance in the Relationship between Type D Personality and Burnout, Moderated by Intrinsic Motivation, with Longitudinal Data.   Note. Coefficients are unstandardized The conditional effects of the focal predictor (TDP) on moderator’s (intrinsic job motivation) values can be seen in Table 3 and Figure 4. Table 3 Conditional Effect of Type D Personality on Burnout at the Values of Intrinsic Job Motivation   Note. SE = standard error; p = p-value; LLCI = lower level for 95% confidence interval; ULCI = upper level for 95% confidence Interval. Discussion In Study 3, replication of results of Study 1 and 2 in a sample especially exposed to burnout and with a longitudinal design was proven. The results confirmed the hypothesized moderated mediations. Then, as in Study 1 and 2, in Study 3 emotional dissonance and self-efficacy to cope with stress mediated the relationship between TDP and burnout, and this time this mediation was maintained with longitudinal data (TDP measured on time 1; mediators and moderators measured on time 2; and burnout measured on time 3); moreover, again, intrinsic motivation reduced the negative impact of TDP characteristics on burnout. Then, robustness of the results was demonstrated with a longitudinal design. The purpose of this research was to determine potential protective and risk factors for burnout in face-to-face jobs and to explore the mediating and moderating relationships that could exist among these determinants. The results corroborate the hypotheses and allow us to highlight both theoretical and practical implications. Regarding Hypothesis 1, while previous research had already shown that dissonance can play a mediating role between other variables (such as negative affect) and burnout (Karatepe & Aleshinloye, 2009), to our knowledge this study is the first to highlight the mediating role of emotional dissonance in the relationship between TDP and burnout. On the other hand, the positive relationship confirmed between TDP and emotional dissonance coincides with previous literature (Bakker & Heuven, 2006; Diestel & Schmidt, 2011; Heuven & Bakker, 2003; Karatepe, 2011; Schaible & Gecas, 2010), which can be explained by the negative perception of people with TDP about themselves, others, and the world (Denollet, 2005). Thus, professionals (e.g., teachers) with high TDP characteristics may perceive a greater need to hide their emotions from users (e.g., students) and their colleagues (e.g., other teachers), facilitating the negative perception of oneself and high levels of emotional dissonance, an additional tension that would lead them more easily to feel burnout (Andela et al., 2016; Denollet, 2005). Then, in accordance with our first hypothesis, people with more TDP characteristics experienced more emotional dissonance; in turn, those two characteristics led them to suffer higher burnout levels. In this sense, the relevance of TDP as predictor of burnout is highlighted, because it plays not only a direct predictive role in this syndrome but also an indirect predictive role, through its activating effect on emotional dissonance, which in turn increases burnout levels in workers. Regarding the second hypothesis, the results confirm the mediating role of self-efficacy to cope with stress in the relationship between TDP and burnout. Again, the relevance of TDP as a risk factor for burnout is noteworthy, because it acts not only as a direct predictive variable of this syndrome but also as an indirect predictive factor, through its negative effect on professionals’ perception of their ability to cope with stressful situations. Although previous scholars have not studied the relationship between TDP and the specific self-efficacy to cope with stress, the results here are consistent with other research that found a negative relationship between TDP and other types of self-efficacy (Molloy et al., 2012; Polman et al., 2010; Shao et al., 2017). In this regard, it seems that the pessimistic vision implied by TDP (Denollet, 2005) can lead individuals to perceive low levels of self-efficacy. In turn, this perception of lack of ability to cope with difficult work situations acts as a risk factor for burnout, as it means that these individuals do not have enough resources to cope with stress; together with perceptions of high workloads, these phenomena have the appearance of burnout (Bakker et al., 2003; Schaufeli et al., 2009). Another explanation of the relationship between low perceived self-efficacy to cope with stress and burnout is provided by Bandura's (1997) cognitive social theory, which stated that people with low self-efficacy tend to avoid situations and tasks. This passive coping would be responsible for the teaching staff not reducing stress and increasing their burnout level. Therefore, our results are consistent with studies demonstrating that low levels of general self-efficacy result in stress and burnout (Federici & Skaalvik, 2012; Molloy et al., 2012; Polman et al., 2010; Sánchez et al., 2006; Shao et al., 2017). In addition, we approach a specific type of self-efficacy more closely related to burnout, self-efficacy to cope with stress, in accordance with Bandura (1997), who explained that specific self-efficacy predicts behaviors better than general self-efficacy. Finally, the moderating role of intrinsic job motivation in the relationship between TDP and burnout (H3) was also confirmed. Thus, the results indicated that the negative effects exerted on burnout by presenting high levels of characteristics related to TDP decreased when staff members were intrinsically motivated for the performance of their job. In this sense, the results demonstrated that high levels of intrinsic job motivation in workers counteracted the negative effects of TDP characteristics on burnout. This result is consistent with previous studies that also found a protective and moderating effect of intrinsic motivation on burnout (Fernet et al., 2010; Trépanier et al., 2013), although, as far as we know, no previous studies have pointed out its moderating role in the relationship between TDP and burnout. This result, very encouraging in terms of theoretical and practical implications, can be explained by Hobfoll's (1989) conservation of resources theory (cited in Karatepe & Aleshinloye, 2009), which affirmed that intrinsic motivation is one of the personal resources to cope with stress and burnout. Limitations and Future Lines of Research Even though the present study provides several contributions to the study of burnout, some limitations that must be considered when interpreting the results should be highlighted. In this sense, data were obtained through self-reports, so results could be biased if participants overestimated or underestimated their burnout level or predictor variables. Therefore, future research should replicate the study by using a longitudinal design and complementing data collection with other methods. Likewise, it would be interesting to know how the variables studied affect other professional groups. Conclusions In conclusion, the confirmation of this study’s hypotheses supports the relationship of studied variables and the predictive model of burnout, demonstrating that all studied variables are relevant in the development and maintenance of burnout. Thus, it was shown that presenting TDP characteristics and experiencing emotional dissonance were risk factors in the burnout process, while self-efficacy to cope with stress and intrinsic job motivation were personal resources that could be used as protective factors. More specifically, in accordance with the confirmation of the mediation exerted by emotional dissonance and self-efficacy to cope with stress on the relationship between TDP and burnout, mediation in turn moderated by intrinsic job motivation, the results demonstrated (a) the relevance of paying special attention to workers with high TDP, because it directly and indirectly influences burnout, by increasing emotional dissonance, which is in turn a risk factor for burnout, and by reducing self-efficacy to cope with stressful situations, which acts as a protective factor for the same syndrome; and (b) the relevance of promoting high levels of intrinsic job motivation in workers through psychosocial interventions, to alleviate the likely negative effects of TDP on burnout. The most relevant results may be that, although having higher characteristics related to TDP is a powerful risk factor for administrators’ and teachers’ burnout levels, this effect decreases when workers have high levels of intrinsic job motivation. Indeed, high levels of TDP had no or almost no effect on burnout when intrinsic job motivation was high. Thus, implementation of psychosocial interventions aimed at improving intrinsic job motivation would be very relevant for professionals, especially for those with TDP characteristics. In conclusion, understanding the determinants that contribute to burnout is a precursor to designing prevention and intervention programs aimed at this syndrome, ultimately contributing to greater physical and psychological health. Conflict of Interest The authors of this article declare no conflict of interest. Cite this article as: Cuadrado, E., Tabernero, C., Fajardo, C., Luque, B., Arenas, A., Moyano, M., & Castillo-Mayén, R. (2021). Type D personality individuals: Exploring the protective role of intrinsic job motivation on burnout. Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 37(2), 133-141.https://doi.org/10.5093/jwop2021a12 Funding: The project and data collection were awarded by the competitive R&D Grant in Occupational Risk Prevention of the Prevent Foundation (Spain). The main researcher of the granted project is Esther Cuadrado. References |

Cite this article as: Cuadrado, E., Tabernero, C., Fajardo, C., Luque, B., Arenas, A., Moyano, M., & Castillo-Mayén, R. (2021). Type D Personality Individuals: Exploring the Protective Role of Intrinsic Job Motivation in Burnout. Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 37(2), 133 - 141. https://doi.org/10.5093/jwop2021a12

esther.cuadrado@uco.es Correspondence: esther.cuadrado@uco.es (E. Cuadrado); rcmayen@uco.es (R. Castillo-Mayen)., esther.cuadrado@uco.es Correspondence: esther.cuadrado@uco.es (E. Cuadrado); rcmayen@uco.es (R. Castillo-Mayen).Copyright © 2025. Colegio Oficial de la Psicología de Madrid

e-PUB

e-PUB CrossRef

CrossRef JATS

JATS